Last time we left off having arrived in Cusco after an exhausting six day’s ride. The ancient Inca capital is located well above three thousand meters and if we hadn’t traversed the passes and the altiplano by car we would have had to adjust to the altitude for a couple of days, which basically comes down to feeling like a covid patient (I remember my encounter with the virus particularly well, missing out on the good weather being helplessly bedridden for the better part of a week). As it was our lungs still needed some practice (turns out sitting in a car doesn’t do anything for your lung capacity) so we decided to hike into the old colonial centre and find out what remains of the indigenous cultural heritage.

Not much, as we soon found out. The Spanish were very convinced of the veracity of their religion (as the saying goes, god is always on the winner’s side) and their zeal in spreading it to foreign lands and helpfully destroying pagan heritage was matched only by their thirst for gold. The irony. As a result, the former imperial capital has preciously little memory of the civilization that ruled the entire Andes just five hundred years ago. By way of comparison we may look at the Roman empire, which in its heyday encompassed a similarly sized territory and many of whose grandiose buildings we may still admire today, despite the fact their glory days are some two thousand years behind us.

So what remains of the Inca’s former splendour? Well, one of their architectural trademarks is easy to spot even as many of the walls have been repurposed of the years: their ability to construct extremely durable walls without mortar or brick, or even regular placement. Through massive human labour and a class of absolutely neurotic masons, they managed to haul and chisel huge diorite boulders into irregular shapes that fit together like a jigsaw. Some stones weigh over a ton yet fit together so closely one cannot insert a piece of paper between them. Hugely impressive to see, especially as the invaders clumsily expanded upon the existing walls with their feeble fired bricks and decaying mortar.

Although a couple of temples remain in the vicinity, the most impressive remnants are the walls of the vast Sacsayhuaman fortress overlooking the city, too massive for the Spanish to take down and build their own and we spent some days chasing down the best kept ruins, often only reachable by hiking.

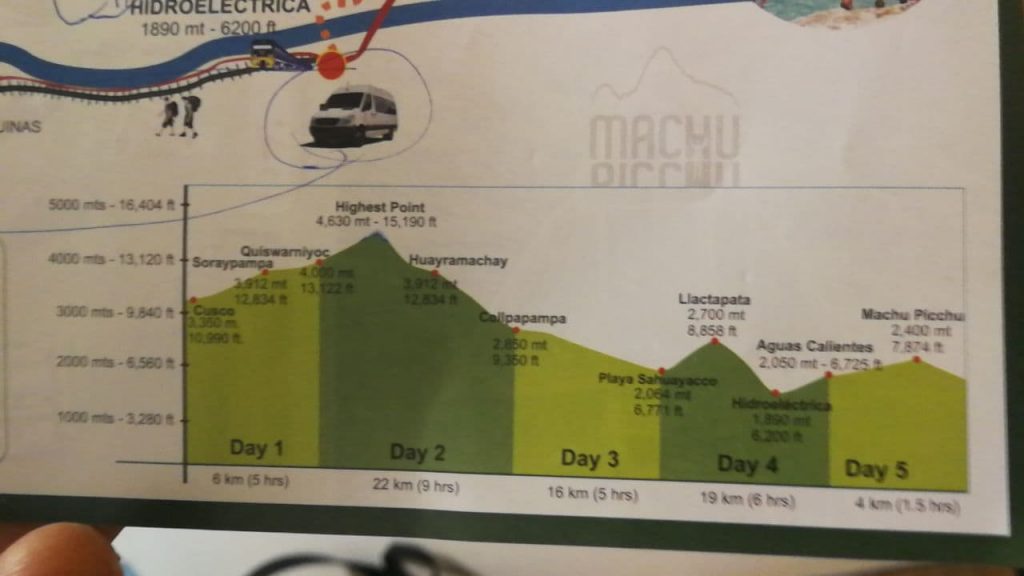

The main goal remained a visit to Macchu Picchu, and although the Inca ruins can nowadays be visited by a combination of bus, train and bus, we had our minds set on the Salkantay trek: a five day trek through the mountains and jungle named for the holy mountain Salkantay which it passes by. Not an easy journey for two barely trained Dutchies: 80 kilometres in total, with the snow-covered pass at 4620 meters as its zenith.

Fortunately we brought our hiking shoes, hiking poles and camping gear. Modern lightweight gear is such a bliss, thinking of my fathers’ old alpineering gear he refuses to throw away. Nowadays I fit a two-person tent, sleeping bag, inflatable mattress, liner and down coat into the bottom of my backpack, totalling out at about 4,5 kg. Small and light enough you can forget about it for the rest of the trip save those fleeting moments wondering whether you will use it at all.

And use it we did. The first day is mostly spent getting from Cusco to the starting village of Soraypampa, hiking two hours to the beautiful Humantay glacier lake and finding a place to eat and sleep in preparation of the next day. Our first night up was spent at around 3900 meters with me reading and Cosette locked in psychological warfare with a hummingbird who refused to be photographed. It was around 2 degrees but sleeping in full clothes including hat made for an acceptable night.

Rain started pouring down around 4 AM and it didn’t let up unfortunately. At 5 we started packing up and had a modest breakfast. I’ll be honest: I was pretty nervous as our roadtrip experiences had taught me altitude sickness wasn’t something I could be cavalier about. Rain was still pouring down hard but by the time we got ready to walk it had turned into snow, surprisingly visible in de grey pre-dawn. “Right”, I thought to myself, “Just 700 meters up and it will all be downhill from there”. I failed to convince myself.

Clad in all the clothes we had (shirt, vest, down jacket, wind jacket) we started the ascent around 6 AM. Despite the snow, visibility was not bad. As the temperature here was above freezing, the melting snow higher up caused rivulets to run down over the path, creating a muddy sludge. Occasionally these streams would blend to form small rivers we had to carefully step our way across. Every now and then, the view would open up as the clouds lifted, giving us a glimpse of the stern Salkantay mountain, gazing down on us with its snowy crown.

This did little to remove my anxiety as a kind of tingling had started in my extremities, the kind that foreshadowed altitude sickness. As we ploughed onwards through the snow it slowly spread until it felt my hands and feet were falling asleep, and it had started to spread to my face. Short dizzy spells started hitting me as well. I’ll be honest, I started to get pretty scared, my mind handing me all sorts of unhelpful scenarios where I would pass out face first in the snow. After some deliberation we decided to keep moving: our guide said this was common enough and I shouldn’t be worried as long as my pace was good and my lungs and pulse were coping. He took a small vial from his pack, opened it, and put a couple of drops on his hands. After shaking vigorously, he blew the emerging vapour into my face, twice. I don’t know what was in that bottle but it seemed to help, a bit. Maybe it was just mentally but I resolved to ignore the tingling in my limbs and just plough onwards.

And before I knew it, I had reached the pass! I had actually made great time in my eagerness to be up and over and as the local had said: as long as your lungs and legs still work you shouldn’t worry too much. The snow had stopped but the icy wind told me it was not a great idea to loiter so I started the descent right away.

Fast forward to six hours later and the reason the Salkantay trek is so famous: after the pass you trek down out of the barren mountainsides and snow, going down 1500 meters, and slowly enter warmer climes, so that you end the afternoon in the jungle, in my case at a nice camping with cold beer and a good meal.

The third day was a nice jungle trek, ending at a refreshing bath in some natural hot springs. Day four is the longest of all: you start by trekking up an old Inca road covering a steep hill. Mind you that the Incas never invented the wheel so all transport was done by people and pack animals so their roads often consist of big stone steps. About 700 meters up you reach the top of the ridge to get a faint glimpse of Machu Picchu on the side of the mountain far away. After a pretty steep thousand meters down your knees are killing you but at least you reached the lowest point now. Half an hour more and you’ll have reached the hydroelectric dam, where you can grab some well-deserved lunch.

And that is where we encounter a very odd phenomenon. Some ten kilometres down the road you’ll find the town of Aguas Calientes (“hot water”), which is basically a tasteless bunch of hotels, restaurants and tourist shops next to the raging river (which ended up flooding half the town the week after we left). To get to Machu Picchu you basically have to sleep there, get a ticket and climb the last five hundred meters up to the ruins early in the morning. This town, although bigger and more luxurious than anything else in a 50km radius, does not have road access. The only way to get there is by train. Inca Rail is a privately owned company which somehow won the tender to build and exploit a train connection between Aguas Calientes and the outside world. Even their budget train option is ludicrously expensive for the amount of distance it covers (the luxury package is close to 400 dollars including a three course dinner enhanced by a performance of local musicians.

That’s when you realize there is no road in order to boost the profits of Inca Rail. Ridiculous, I know. But it gets better: the locals don’t take the train at all, because it is much cheaper to walk – on the rails! We did the same and you basically hike for two hours on the train tracks, admiring the river, the jungle and the impressive exhibition of signs trying to convince you are in mortal peril and should walk back and buy a train ticket if you value your life at all.

With this many people hiking to and fro, local entrepreneurs soon realized it would be quite nice to be able to buy a bottle of water along the way. Or a beer. Or a meal. Which means you pass by a lot of small restaurants by the side of the train tracks, unavailable for the actual train (which doesn’t stop anywhere in between), solely for the convenience of the railway interloper!

Twenty-five kilometres is a long walk in the mountains so we were pretty exhausted when we finally reached the town. I actually fell fast asleep right after I demanded another room because the toilet wouldn’t flush. The next day we got up at four to hike through the pre-dawn up the stairs to get to the ruins at six. The mountain wasn’t through with us though: just after we left, it started pouring down like there was no tomorrow, and that day I learned that climbing steep jungle Inca stairs in the dark wearing a poncho is really no fun at all. Fortunately it stopped raining around seven, after which we were left seeing a big blank wall of fog. We were about to hike back and accept our misfortune when the fog suddenly lifted and the incredible sight of Machu Picchu came into view. I have seen a lot of good sights but those shreds of fog dissipating, revealing the majestic temple complex and the imposing mountain range framing it is truly a sight to behold. The five day hike really makes it feel like a pilgrimage (even more so because the Inca emperor himself would summon dignitaries from far and wide to make the long trek to the sacred temple complex) and I can heartily recommend it to anyone who wants to visit the ruins.

Thanks if you made it this far and find out next time whether we managed to bring our car back to Lima in one piece! Please leave a comment and let me know what you think. Cheers!